The Ultimate Guide to Using OC Spray for Self-Defense

OC Spray for 1st Amendment Auditors

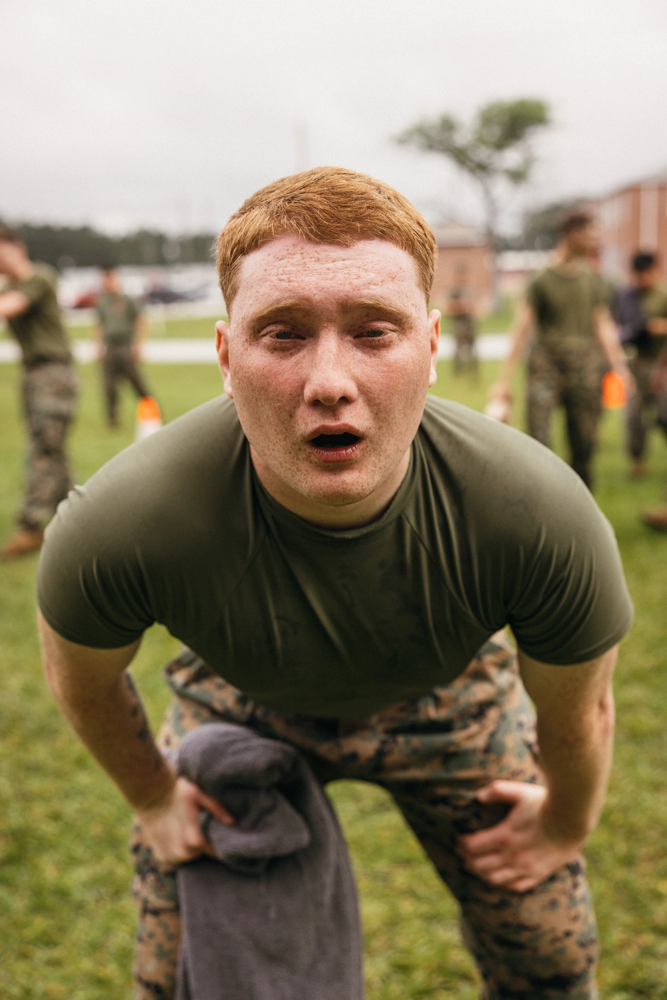

A U.S. Marine after OC spray exposure during training. Pepper spray’s inflammatory effects cause intense burning, eye closure, and discomfort without lasting harm

Introduction to OC Spray

.Oleoresin Capsicum (OC) spray – commonly known as pepper spray – is a defensive aerosol derived from the “hot” oils of cayenne and other chili peppers. It is classified as an inflammatory agent, not merely an irritant. Upon contact with a person’s eyes, skin, or mucous membranes, OC spray causes an involuntary sensation of burning pain: capillaries dilate and tissues become inflamed, leading to redness, swelling, and immediate eye closure[1]. Despite the intense temporary pain and panic it induces, OC spray does no permanent tissue damage – there is no actual burning of the skin, only the feeling of heat. In fact, medical evaluations have found pepper spray to be generally safe with negligible long-term effects; there’s no known lethal dosage for humans under normal use[2]. Even if someone were saturated in OC spray, it would be extraordinarily unlikely to cause death by toxicity alone[3]. (Notably, rare fatalities associated with pepper spray typically involved other complicating factors like asthmatic reactions, drug intoxication, or dangerous restraint positions – not the OC agent itself[2].)

Why Choose OC Spray? For civilians and law enforcement alike, pepper spray offers a powerful blend of effectiveness and safety that makes it one of the most recommended less-lethal tools:

- Highly Effective at Stopping Threats: OC spray is not magic, but it comes close. Studies and real-world police data indicate pepper spray reliably incapacitates or subdues aggressive individuals about 85–90% of the time[4]. In an International Association of Chiefs of Police study, OC spray resolved confrontations in up to 90% of cases, significantly reducing injuries to officers and suspects compared to higher-force interventions[4]. While determined attackers can sometimes fight through the effects, they will still be impaired – eyes squeezed shut, vision blurred, skin burning, and lungs heaving. Even when OC doesn’t instantly drop an attacker, it almost always diminishes their physical abilities and buys you time. This high success rate means pepper spray can avert many assaults without the need to escalate to firearms or physical brawling.

- Safest Use-of-Force Option: Pepper spray is widely regarded as one of the lowest-risk self-defense tools in terms of lasting injury. Research (including a 2025 literature review) finds that when police use OC spray, suspects are less likely to be injured than with any other force option – the risk of significant injury is the lowest among common use-of-force methods[5]. By causing pain and temporary incapacitation without blunt trauma or penetration, pepper spray avoids the fractures, lacerations, or worse that can occur with batons, bullets, or even hard empty-hand strikes. Injuries from OC tend to be minor and short-lived (skin and eye irritation that fully resolves)[6]. Importantly, you as the defender are also safer – controlling a threat at a distance with spray means you may not have to wrestle on the ground or risk serious harm. This has led some experts to call pepper spray the most humane force option available for both the defender and the aggressor.

- Prevents Escalation to Lethal Force: By effectively handling threatening situations early, OC spray can stop an incident from escalating to a point where lethal force might seem necessary. Self-defense instructors often point to hypothetical scenarios where a tragic shooting could have been avoided had pepper spray been used in time. For example, consider the notorious case of George Zimmerman and Trayvon Martin – had Zimmerman carried pepper spray and deployed it at the first sign of physical danger, it’s conceivable the confrontation might have ended without lethal force. While we can’t rewrite history, the lesson is clear: judicious use of OC spray as an early deterrent can defuse aggression and reduce the need for gunfire or other higher-force responses later. In essence, OC gives you a critical intermediate option on the force continuum – one that can bridge the gap between shouting and shooting.

- Non-Lethal and Safe: Pepper spray is categorically non-deadly. It is not poisonous, and it causes no lasting internal damage. You could literally take a bath in a vat of OC and, aside from extreme discomfort, suffer no lethal effects. There is no documented lethal concentration of pepper spray from inhalation in humans[3]. Unlike Tasers or chokeholds, which carry a (very small) risk of lethal complication, properly used pepper spray has never been conclusively shown to directly kill. Subjects exposed to OC might experience intense burning sensations and panic, but once they recover (usually within 30 minutes to an hour), they return to normal with no permanent injury. Authorities consider OC spray a “less-lethal” weapon with a wide margin of safety – people routinely recover without need for medical attention[7]. (Even animals like dogs and bears are regularly repelled with high-strength OC formulations with no lasting harm, underscoring its relative safety.) In the rare tragic cases where suspects died after being pepper-sprayed, coroners almost always found the cause of death to be something else (drug overdose, severe asthma, positional asphyxia, etc.), not the OC itself[8]. Pepper spray’s non-lethality is a key reason it’s so broadly legal and accepted – one could argue it’s more “humane” than even a hard punch, which might crack a skull or rib.

- Demonstrated Effectiveness in Law Enforcement: Police forces around the world have embraced OC spray because it works. In real policing scenarios, pepper spray has been documented to achieve compliance or incapacitation in the vast majority of uses. For instance, U.S. police data (as summarized by a Dutch study) noted that pepper spray use was successful in subduing suspects in 90% of cases, concomitantly reducing injuries to both officers and arrestees[4]. Canadian policing studies likewise report that OC spray has one of the highest “success rates” in resolving resistive encounters without further force[5]. Simply put, if you use pepper spray on an attacker, there’s an overwhelming chance you will significantly halt or hinder their attack. It’s not a guarantee – nothing in self-defense is – but few other non-lethal tools come close to OC spray’s track record of stopping power. Users should remember, of course, that no tool is 100%; a drugged or enraged individual might power through the burn, but they will still be affected (perhaps squinting, coughing, and slowed). Pepper spray gives you a fighting chance in situations where empty hands might not, and without the finality of a firearm.

- Broad Utility for All Skill Levels: One of the great advantages of OC spray is its accessibility – it can be effectively used by people of varying strength, size, or training. You don’t need years of martial arts experience or special aim under pressure; a basic introduction and a practice spray or two can make anyone competent with OC. This makes it an ideal choice for civilians of all walks of life, from college students to elderly individuals. Even those who carry a firearm for self-defense often carry pepper spray as well, for situations that don’t justify lethal force. And for those who cannot or choose not to carry a gun – such as many high school and college students, people in jurisdictions with strict gun laws, or anyone uncomfortable with lethal weapons – pepper spray provides a legal, relatively simple means of protection. Carrying OC spray can also help instill a defensive mindset. For example, young people going off to college (especially women) are often encouraged to carry pepper spray; doing so helps them think about personal safety, stay aware of their surroundings, and have a plan should danger arise. In short, pepper spray is an equalizer – it doesn’t matter if you’re not physically imposing; a small can of OC can deter or disable an aggressor long enough for you to escape.

- Less Legal Liability (Good Optics): Using a non-lethal defense like pepper spray can put you on much firmer legal and moral ground if a situation later escalates. Prosecutors and juries generally recognize that someone who tries a milder measure first and only then resorts to lethal force truly feared for their life and had no other choice. Demonstrating that you attempted to de-escalate or disable the threat with OC spray can be a powerful fact in your favor in court. It shows you weren’t looking to harm someone; you were trying to stop them with minimal necessary force. This could significantly improve your legal standing if, for instance, you ended up having to use your firearm when the spray wasn’t enough. Self-defense experts often point out cases where defenders got in legal trouble for shooting an unarmed assailant; had they used pepper spray first, the narrative could be very different. As one analysis of a self-defense case noted, “If the defender had tried pepper spray first and it failed, that would have gone a long way toward undercutting the prosecutor’s portrayal of him as a trigger-happy ‘killer’”[9]. In other words, deploying OC spray shows restraint. If worse comes to worst, you can articulate that you did everything possible to avoid lethal force, which can sway both investigators and jurors to view your actions as reasonable.

Finally, it’s important to introduce the concept of “Managing Unknown Contacts” (MUC), a term from defensive training that will be a running theme in this guide. Unknown contacts are people you don’t know who approach you – possibly benign, possibly malicious. MUC refers to strategies for handling such approaches safely. A key element is “Pre-MUC”: detecting and addressing potential threats at a distance before they become direct confrontations. This means maintaining a high level of awareness and heeding early warning signs of danger. A popular maxim is: “If something doesn’t look right, it isn’t right.” Trust that gut feeling. As one instructor puts it, “If that $#!% don’t look right, that $#!% ain’t right” – don’t let politeness or denial override your instinct[10]. Pre-MUC involves things like keeping an eye on who’s around you, maintaining distance from strangers, and positioning yourself for an easy exit if needed. In practice, if you spot a sketchy individual or behavior before they get close, you might use verbal commands or the deterrence of OC spray (displayed or at the ready) to ward them off. The upcoming sections will delve deeper into these preventive measures. Remember: The best fight is the one avoided. OC spray is most effective when used early, at the first hint of real danger – not when an attacker is already on top of you. With that foundation in mind, let’s explore how to choose the right OC spray and carry it, and then how to use it tactically as part of a smart self-defense strategy.

Selecting the Right OC Spray Product

Not all pepper sprays are created equal. There are different formulations, spray patterns, and quality levels on the market. To use OC spray effectively, you need to choose a good product and understand its capabilities. Here we’ll cover the types of sprays, what potency metrics to look for, which products to avoid, and other purchasing tips.

Types of Spray Patterns: OC spray canisters disperse their contents in a few different patterns. The main types are stream, cone (mist), foam/gel, and high-volume fogger. Each has pros and cons:

- Stream (Straight Stream): This shoots a concentrated liquid stream (think squirt gun) directly at the target. A streamer has the longest range of the common types – often reaching 10–15 feet or more[11]. It is also the least susceptible to wind; a strong stream is less likely to blow off course, and it’s easier to avoid exposing yourself or bystanders to blowback. Another benefit is precision: you can target a specific individual in a group by aiming the stream, which is useful for avoiding hitting others. Downside: A stream’s effectiveness depends on accuracy. You need to hit the attacker’s face, especially the eyes, directly. Because the liquid is not fine aerosolized droplets, an assailant might not inhale much of it if you only hit their torso or if they hold their breath. Without inhalation, OC loses some effect (the respiratory burn and coughing will be less)[12]. In short, stream sprays excel at distance and outdoor use, but you must have decent aim under stress. They are often preferred by law enforcement for their range; however, for civilian defense at very close range, other patterns might incapacitate faster.

- Cone (Mist) / Fogger: Often called cone, mist, or aerosol spray, this pattern expels the OC as a fine mist or cloud, similar to a hairspray can. It creates a wider cone-shaped plume of irritant that’s hard to avoid. The big advantage here is that it’s very easy to hit the target – you basically “spray in their general direction” and the mist will engulf the attacker’s face. Fine droplets are easily inhaled, which means even if an aggressor’s eyes are only partially hit, they will breathe the OC into their nose and lungs, triggering coughing, choking, and a burning throat[13]. Mist sprays tend to incapacitate faster than streams because of this immediate respiratory involvement. Downsides: The effective range is shorter – typically about 6–8 feet for many cone sprays[14]. The spray cloud can also be significantly affected by wind, dispersing or even blowing back toward you. Additionally, cross-contamination is a real risk: that cloud doesn’t discriminate. If you spray a cone indoors or in a crowd, everyone in the vicinity (including you and any friendlies) may get a dose of OC[14]. Eyes, noses, and even skin of bystanders can feel the burn. In an open outdoor setting with a light breeze, you also must be mindful of which way the mist will drift. Despite those drawbacks, cone sprays are very effective at close quarters and under panic – when fine motor skills may fail, a wide spray increases your odds of tagging the threat.

- Foam / Gel: These are OC formulations mixed with a gel or foam carrier, which eject in a thick, sticky foam blob (often resembling shaving cream) or a viscous gel stream. The foam/gel is designed to stick to the target’s face, making it hard to wipe or wash off quickly. The primary benefit is minimal cross-contamination: the OC doesn’t become an airborne cloud, so it won’t affect others nearby or fill a room. This makes foam or gel a good choice for indoor use or for users extremely concerned about hitting bystanders (e.g. maybe you have to spray someone when you’re holding a child – you don’t want mist blowing into the child’s eyes). It’s also good in wind, since there are essentially zero aerosolized droplets to blow back. Downsides: Historically, foam/gel was found to be slower-acting. Because it doesn’t immediately atomize and get inhaled, a motivated attacker might have a second or two longer to keep coming. The foam must contact the eyes or be absorbed through mucous membranes to take full effect, and thick foams sometimes took a bit longer to induce the reaction[15]. Early foams also had the issue of an attacker grabbing handfuls of foam off their face and flinging it back at the defender (yes, it’s happened!). The good news: modern pepper gels and foams have improved. Many are quite fast-acting and harder to counter. For example, Sabre Red’s pepper gel claims the same stopping power as their sprays, but with the gel format. Nonetheless, foam/gel requires precise hits – you really need to plaster the assailant’s eyes with it. If you hit their chest or they turn their face, the OC might not reach mucous membranes immediately. Use foam/gel in scenarios where you absolutely cannot afford any contamination of others (say, on an airplane or in a dorm room), and practice aiming for the eyes. Otherwise, a cone or stream is often a better general-purpose choice[15].

- Foggers (High-Volume Fog): These are large canisters (often 8–16 oz or more, sometimes sold as bear spray or riot control spray) that release OC in a thick fog bank. Think fire-extinguisher style output. A fogger can fill a room or saturate an area with pepper irritant. The intended use is for multiple attackers, crowd control, or animal defense (bear spray is essentially an OC fogger formulated for bears). The benefit is maximum area coverage – it will create a wall of pepper mist that no one wants to push through. Range is moderate (bear sprays typically reach 20–30 feet in a cone-shaped fog). For personal defense, foggers are overkill in most cases and come with the highest risk of self-contamination – you’re basically bathing the environment in pepper spray. These are not for casual carry (too large to pocket) but might be kept at home for riot defense or by hikers in bear country. One creative use taught in some seminars: a small household dry-chemical fire extinguisher can double as a fogger-like defensive tool (more on that later). Overall, unless you anticipate a home invasion by a mob or need bear spray for wilderness, a fogger isn’t a typical EDC pepper spray for civilians.

Key Performance Indicators (Potency): When comparing OC spray products, the marketing can get confusing – Scoville Heat Units, OC percentage, major capsaicinoid content – what matters? Here’s how to cut through the hype:

- Major Capsaicinoid Content (MC or MC%): This is the most important number. Major capsaicinoids are the actual heat-bearing chemicals (like capsaicin and related compounds) that produce the effects. MC% tells you the true potency of the formulation. High-quality pepper sprays will list this percentage on the can or in their specs. Look for sprays in the 1.0% to 1.4% MC range. For example, many police-grade OC sprays are around 1.33% MC. That might not sound high, but 1.33% of pure capsaicinoids is extremely hot – plenty to incapacitate a person. In fact, 1.3% MC is arguably “maximum strength” for human use (and as a comparison, bear sprays by law max out at 2% MC)[16]. Some civilian sprays advertise 0.5% or 0.7% MC; those are decent, but stronger is usually better up to a point. The key is that MC% directly indicates the heat intensity of the spray in the can (after dilution and propellants, etc). It’s a lab-tested value. Pro tip: Only trust products that disclose their capsaicinoid content. If a brand doesn’t tell you the MC% (or at least Scoville or OC% – something), be wary. Reputable manufacturers provide this info or the product’s Safety Data Sheet (SDS) so you know what you’re getting.

- Scoville Heat Units (SHU): This is a measure of pepper heat traditionally used in the food industry (e.g. habaneros are X SHU). You’ll see sprays brag like “2 million SHU!” or “5.3 million SHU!” However, SHU can be misleading in isolation. Often, the SHU number refers to the raw pepper or oleoresin used before it’s diluted in the can. For instance, a company might use 5 million SHU pepper extract, but then dilute it 1:10 – resulting in a much lower effective strength per spray. SHU is determined by a subjective taste test methodology and doesn’t directly convey how the spray will feel when used. As a rule of thumb, you do want a pepper source rated at least 1 million SHU or more[17] (most quality sprays use 2–5 million SHU base). But don’t be wowed by an enormous SHU claim without context. A 5 million SHU extract at 1% concentration is less potent than a 2 million SHU extract at 3% concentration, for example. SHU matters, but only in conjunction with concentration.

- OC Percentage (% OC): This tells you what portion of the can’s contents is oleoresin capsicum (the pepper resin). Common concentrations range from 5% to 15% OC, with some as low as 2% and some “military” ones claiming 20% or more. Here’s the catch: a higher percentage does not guarantee a stronger effect, because it depends on how hot that OC is. A 10% OC spray made from weak peppers might be far less effective than a 5% spray made from very hot peppers. In general, though, a certain minimum percentage is useful to ensure duration of effect. A spray that is at least 5% OC is often recommended for a solid 20-30 minutes of effect[18]. Higher percentages (like 10%) might extend the burning sensation longer (perhaps 45+ minutes), which could be good or bad depending on your perspective (bad for the bad guy, good for you, unless you get it on yourself!). Focus on MC%, but use OC% as a secondary factor. If two sprays have similar MC, the one with higher %OC will usually maintain its effect longer (more oily resin on the skin). Just be aware of marketing tricks: some products boast “10% OC!” in big letters, hoping you’ll equate that with strength. But unless they also tell you the MC% or SHU, you don’t really know what that 10% means. It could be 10% of fairly mild pepper extract. Bottom line: Don’t be swayed by percentage alone – find the MC%. Many experts consider MC (major capsaicinoids) the gold standard because it’s a direct measure of the active components[19].

- Spray Pattern and Range: As discussed above, know what pattern (stream, cone, etc.) the unit uses. Range can be important – check the product specs or tests. A keychain mini-spray might only reach 5–6 feet effectively[20], whereas a larger unit could reach 12–15 feet[21]. Generally, more range is better (you want to engage an attacker before they’re within arm’s reach). Stream sprays usually have the farthest range, then gels, then cone mists. Ensure the range listed meets your needs, and remember that real-life factors like slight wind or adrenaline might reduce it a bit.

- Spray Volume and Duration: How many shots can the can deliver? And how long will it spray if you hold it down continuously? Pepper sprays come in various sizes (common ones are 1/2 oz, 1 oz, 1.5 oz, 2 oz for personal carry). A typical 1/2 oz keychain model might have ~5–10 one-second bursts worth of OC. A 2 oz can might have 15–20 short bursts. More volume gives you more attempts and the ability to spray longer if needed. However, larger cans are bulkier to carry (balance is key). For most civilians, a 1 to 2 oz can is a good balance – these often contain around 25–30 seconds of total spray time and can be used in multiple incidents if you give a quick burst per incident[22][23]. Always factor in that you might miss or need multiple bursts under stress, so having extra capacity is reassuring.

Avoiding Ineffective or Unproven Products: Unfortunately, the pepper spray market isn’t strongly regulated (for civilian formulas), which means there are some gimmicks and bad advice floating around. Steer clear of these common pitfalls:

- Wasp Spray Myth – Don’t Do It: You may have heard the internet advice: “Carry wasp spray instead of pepper spray – it’s just as effective and shoots farther!” This is terrible advice. Wasp/hornet spray is not a proven self-defense tool. Firstly, it’s not designed for humans – wasp spray is a neurotoxic poison meant to kill insects, not stop a motivated attacker. There is zero evidence that wasp spray will reliably deter or disable a person. In fact, there have been cases where people tried using wasp spray for self-defense and it completely failed to stop the attacker[24]. One documented home invasion saw the homeowner blast the intruder with wasp spray to no effect – the assailant kept coming, undeterred[25]. In contrast, quality pepper spray has an 85-90% success rate. Wasp spray’s long-range stream (20+ feet) might seem attractive, but realize that most attacks happen at close range and you won’t have a chance to shoot from that far. More importantly, spraying someone with a pesticide in the face could have legal repercussions. It’s an off-label use of a toxic substance; a prosecutor could argue it’s aggravated assault with a poison. As one firearms instructor quipped, imagine explaining to a jury why you used “Real-Kill Wasp & Hornet Killer” on a human[26]. It just sounds malicious. Stick to products explicitly made for self-defense – pepper spray, not bug spray.

- Mixed CS/CN Tear Gas Blends: Some defensive sprays advertise a cocktail of OC (pepper) plus CS or CN (tear gas), sometimes with a dye. The idea is a combo of irritants. In practice, these are usually inferior to pure OC spray. CS (orthochlorobenzalmalononitrile) is a crystalline tear gas that primarily causes tearing and irritation. It can be effective for crowd control in enclosed areas, but CS takes time to work – often 20–60 seconds for full effect, which is an eternity in a violent encounter. When sprayed directly in the face in outdoor conditions, CS and the older CN gas often don’t incapacitate quickly enough. Moreover, CS/CN rely on pain compliance (causing stinging in eyes and skin), and many attackers (especially if enraged, on drugs, or mentally ill) can fight through that pain[27]. OC’s inflammatory effect is more reliable regardless of pain tolerance. CN (chloroacetophenone), the original “Mace” compound, is even worse – it’s considered relatively toxic (can be lethal in high concentrations in confined spaces) and mainly just makes the eyes water. People can still see through tears and continue attacking. Meanwhile, adding CS or CN to a spray dilutes the OC concentration to make room in the can. So you end up with, say, 50% OC strength plus 50% CS that might not even kick in during the fight. For these reasons, avoid pepper sprays that include CS/CN. They introduce more legal complexity too (some states prohibit civilian tear gas). A quality OC spray has all the stopping power you need; extra chemicals can actually reduce its efficacy. (For animal defense, it’s also notable that CS/CN have little effect on dogs or wild animals – dogs and horses are largely unfazed by tear gas, whereas pepper spray works on them. This underscores how much more universally effective OC is.)

- Unknown or Unregulated Brands: Because pepper spray is not federally standardized for strength, there are some sketchy brands out there. You might find cheap canisters at a flea market or online that have no listed ingredients or SHU ratings. Do not trust your life to an unknown $5 spray with no data or pedigree. Stick to reputable manufacturers that law enforcement and consumers trust – for example, Sabre, Fox Labs, Defense Technology, Mace Brand, POM, Kimber PepperBlaster, etc. These companies invest in quality control. Look for an expiration date and lot number on the product. If a spray doesn’t have an expiration date, that’s a red flag (all good sprays do, because potency and pressure degrade over time). Also, check that the product has an SDS (Safety Data Sheet) available – that’s a sign the company is providing info about contents. There have been cases of off-brand sprays containing lower concentrations than advertised, or even using solvents that evaporate and reduce effectiveness. Don’t risk it. Buy from a known source (not some dubious Amazon seller with a brand you’ve never heard of).

- Carcinogenic Carriers/Solvents: Some older or low-quality OC formulations used solvents that are not ideal – for example, methylene chloride or other chemicals that could be carcinogenic or very harsh. Modern top-tier sprays use safer carriers (like water, alcohol, or propylene glycol mixes) and safe propellants (like nitrogen or CO₂). While specifics might not be readily available on every product, another reason to stick with reputable brands is to avoid any unnecessary exposure to nasty chemicals. The whole point is a safe non-lethal tool – you don’t want to be dousing someone (or yourself) with a carcinogen if it can be helped. When possible, glance at the SDS: if you see known hazardous chemicals beyond the OC, consider a different product.

- Overly “Hot” Percentages (Excess Strength): It might be tempting to seek out the “hottest” pepper spray on the market. You’ll see some brands brag of 3% major capsaicinoids or 5 million SHU at 10% OC, etc. Be cautious here. Remember that 1.3% MC disables humans effectively – anything much beyond that may only increase the chance of causing unnecessary injury (or legal trouble) without meaningfully increasing stopping power. For context, bear spray used on 800-pound grizzlies is capped at 2% MC[16], and it stops them in their tracks. Human attackers absolutely do not require higher concentrations; they’ll go down (or at least wish they had) with standard formulations. Using an ultra-high concentration pepper spray on a person might be seen as use of excessive force if it causes atypical injury. There’s also a practical issue: extremely high concentration sprays can thicken the resin, clog nozzles, or slow the spray stream. Many experts agree that around 1%–1.4% MC is optimal – beyond that yields diminishing returns. So don’t get caught up in an arms race of percentages. A well-placed burst of 1.3% will do the job. (And if it doesn’t, 3% likely wouldn’t have either.)

Product Quality and Reliability: Once you’ve chosen a type and strength, you want to ensure the unit will work when needed. Pay attention to these factors:

- Expiration Date and Replacement: Pepper spray cans don’t last forever. They are sealed pressurized devices – over time, seals can deteriorate and propellant can leak, reducing pressure. The OC resin itself also might separate or settle. Most sprays have an expiration date about 3 to 4 years from manufacture. However, a strong recommendation is to replace your carry pepper spray annually, or at least every 18–24 months[28]. Why so frequent? Because you want absolute confidence that it will spray at full pressure. Heat, cold, and jostling (like from daily carry) can hasten leakage. If you carry a unit on your keychain or in your pocket every day, it experiences temperature swings and possibly impacts; changing it every year is cheap insurance. If your spray is kept in more stable conditions (say in a climate-controlled home, untouched), you could go up to the marked expiration date (typically 2–4 years). At the minimum, do a function test every 6 months or so: take it outside, and give a very quick tap of the trigger to see if it still emits a strong spray. (Be mindful of wind and location when testing!) Many instructors advise shaking your pepper spray canister once a month to keep the contents mixed[28]. Also ensure nothing has clogged the nozzle (some carry cases can get lint in the opening). Never use an expired spray for defense – it might not have pressure when you need it. OC spray is relatively inexpensive, so swap in a fresh can regularly.

- Canister Design and Propellant: Newer pepper spray units often have better delivery systems. Some use nitrogen propellant or CO₂ which maintain pressure more consistently through temperature changes. Older aerosol designs using hydrocarbons or compressed air may be more prone to pressure loss over time. Additionally, certain brands feature 360° spraying canisters (for example, Sabre’s Crossfire technology) that can spray at any angle, even upside-down. This is a big advantage in a dynamic self-defense situation, where you might not have a perfect upright stance. Look for high quality valve construction – a well-built canister is less likely to leak prematurely. Also consider the safety mechanism design (more on safeties in the next section on carrying). Some units have clever flip-top safeties that prevent accidental discharge but allow quick use. Generally, you get what you pay for: a $12–20 unit from a known brand will likely have better engineering than a $5 generic. Given that reliability is paramount, spend the extra few dollars for a trusted brand and model. Your life might depend on one squeeze of that trigger working.

- Storage Conditions: Treat your pepper spray kind of like medication – store it in a cool, dry place when you can. Extreme heat can cause pressure build-up (in worst cases, causing the can to leak or burst). For example, don’t leave your OC canister on the dashboard of a car in Phoenix in July. If you must leave it in a vehicle, keep it out of direct sun and maybe inside a contained pouch (and be aware it could depressurize). Extreme cold can also reduce the pressure or even cause the propellant to fail to aerosolize properly. So don’t leave your pepper spray in below-freezing temps for long periods. Everyday carrying on your person is fine – body heat and normal outdoor temps won’t significantly hurt it. Just avoid the truly extreme environments for storage. If a can has been stored in adverse conditions (say a hot car) for months, I’d lean toward replacing it or at least testing it. Also, do not puncture or burn an OC canister (obvious perhaps, but worth stating) – it’s pressurized and flammable. Lastly, store out of reach of children; you don’t want a kid playing with it and spraying themselves or others.

- Legal Considerations: Before you purchase or carry pepper spray, make sure it’s legal to do so in your area and that your chosen product meets local regulations. Pepper spray laws vary by state (and country). In the vast majority of U.S. states, OC spray is legal for adult self-defense, but some states impose limits on canister size or formula. For example, California limits civilian-carried pepper spray to 2.5 oz or less per canister[29]. Wisconsin requires OC concentration of no more than 10% and bans any mixtures containing CS/CN; it also limits size to 2 oz and stipulates a safety feature on the device[30]. Michigan allows up to 1.2 oz and 10% OC. New York limits canisters to about 0.75 oz, and you must buy it from a local licensed firearms or pharmacy dealer (no online orders)[31]. Some jurisdictions (like Washington D.C.) technically require registration of pepper spray with the police (though this is often not enforced)[32]. It’s on you to know your local law – most of these regulations are easy to comply with (just buy a legal size, etc.). Also note, age restrictions: typically you must be 18 or older to possess pepper spray (with some exceptions for minors with parental consent in certain states). Felons and certain convicted offenders are prohibited from possessing pepper spray in a few states. Internationally, some countries treat pepper spray as an illegal weapon, while others allow it – so research if you plan to travel. The takeaway: check your state’s laws (a quick search for “[Your State] pepper spray laws” or consulting the product site – many list state restrictions). As a general guide, a small OC-only spray under 2 oz will be legal in most places. Once you have it, use it only in lawful self-defense – deploying pepper spray offensively or as a joke can result in assault charges. Treat it seriously, the same way you would any defensive weapon.

Carrying and Staging Your OC Spray

Owning a good pepper spray won’t help if you can’t access it in time during an attack. Proper carry and “staging” (getting it ready) are crucial. Here are best practices to ensure your OC spray is there when you need it:

- Keep It Readily Accessible: This sounds obvious, but many people buy pepper spray and then toss it in the bottom of a purse or glove box. In an emergency, you won’t have time to dig around. You should carry your OC in a consistent, quickly accessible spot on your person whenever feasible. Great options include: clipped to the inside of a front pants pocket, in an outer jacket pocket, or on a keychain (if you typically have keys in hand). If you carry on a keychain, be careful that it doesn’t disappear into a deep bag – consider a quick-release keychain that you can detach and have the spray in hand as you walk. Some pepper sprays come with pocket clips or belt holsters – use them if they fit your lifestyle. The key is, you should be able to draw and fire the spray within about 1–2 seconds when under stress. If it takes you five seconds of rummaging, it’s too slow[33]. Try a timed drill: from however you normally carry it, see how long it takes to get it out, finger on trigger, safety off. If it’s more than a couple seconds, rethink your carry method[33]. Many instructors advise against keeping pepper spray loose in a purse because in a panic you might not find it in the clutter. If you must purse-carry, dedicate a particular easy-to-reach pocket of the purse for the spray, and practice retrieving it. In short: accessibility is king. It’s better to slightly compromise on canister size or concealment in favor of quick access. A small unit in your hand beats a large unit in the bottom of a backpack when it comes to stopping an imminent threat.

- In-Hand Carry in Transitional Spaces: It is socially acceptable (and tactically wise) to carry your pepper spray in hand in certain situations, especially “transitional spaces” where attacks often happen. For example, when walking through a dark parking lot to your car, or along an isolated sidewalk at night, go ahead and hold your pepper spray at the ready. Unlike a gun or knife, holding pepper spray won’t generally alarm people – it’s a small innocuous canister that most won’t even notice, and even if they do, it doesn’t carry the same stigma. By having it in hand, you eliminate the draw time entirely. If someone suspicious approaches, you’re already armed with OC. If nothing happens, no harm. Think of it as similar to having your car keys in hand when you approach your car – it’s about being prepared and reducing reaction time. Many assaults occur when people are walking to or from their car, or between public transport and home. Those are prime times to keep your spray in hand. You can even adopt a covert ready position: hold the canister in a loose grip with the nozzle pointing outward concealed by your curled index finger, so it’s not obvious you have something. That way you retain some element of surprise but can deploy instantly. The bottom line: when in doubt, get it out. There’s no downside to carrying the spray in your hand if you feel the slightest concern about the environment. Better to have it ready than to be caught off-guard fumbling for it.

- Use a Positive Safety and Proper Grip: Most pepper sprays have some form of safety mechanism to prevent accidental discharge (nobody wants a can firing in their pocket!). Common safeties are: a flip-top cap (spring-loaded cover you flick aside with your thumb), a twist lock (you rotate a knob or the nozzle to arm it), or a slide button safety. When choosing a spray, favor designs that you can quickly and positively disengage under stress – generally, flip-top or slide safeties are faster than twist locks. A popular style is the flip-top (also called a Pop-up): your thumb flips the cap up and is then in position to press down on the actuator. This type is great because you can feel when it’s indexed forward and it largely prevents backward discharge onto yourself. Avoid extremely tiny keychain designs that have complicated twist-off safeties or those hidden in hard-to-open cases. Greg Ellifritz, a self-defense instructor, recommends keychain models that are fully encased in plastic with a simple sliding safety, noting that older leather holster styles with twist safeties are too slow[34][35]. Whatever you carry, practice disengaging the safety by feel. You should be able to unlock and fire the spray with one hand, without looking at it. Many training units and inert sprays are available for practice – it’s worth getting one to rehearse the motions (and to see the spray pattern). Also, maintain a proper grip: wrap your fist around the canister with your thumb on the trigger. Do not grip it with your index finger on top – that grip is weaker and less accurate[36]. The thumb-down grip (like a small flashlight grip) tends to be best for control and also keeps the spray oriented correctly. We’ll cover more on grip and aiming in the tactics section, but when carrying, get used to holding it in a thumb-ready position. A well-designed unit with a good safety (for example, the Sabre Red flip-top or POM’s twist-top with indicator) will greatly reduce the chance of an accidental discharge in your pocket while still allowing quick use.

- Secure It, But Don’t Hide It Too Deep: When carrying pepper spray on your person, you want it secure enough that it won’t fall out or be knocked away, but not so secured that you struggle to pull it free. If you use a pocket clip, periodically ensure the tension is good so it doesn’t slide off. If you keep it in a pocket, consider dedicating that pocket to just the spray (keys or other objects can snag or slow your draw). Holsters (like those that attach to belts) should have an open top or a very minimal retention strap. Many pepper spray belt holsters have a basic snap flap – practice opening it quickly if you use one. One trick: some runners or outdoors folks carry a pepper spray in a velcro armband or wrist strap – this can be effective as it’s literally on-hand. Choose bright-colored canisters or add some reflective tape if you’ll carry during low light while jogging; you don’t want to drop it unseen. At home, store a can in a consistent accessible place (e.g., by the front door or nightstand) in case you need to grab it in a hurry when investigating a strange noise but don’t feel the situation warrants a firearm. Think about staging pepper spray in certain scenarios – for example, if you hear someone outside at night, you might grab your OC in hand as you check (staying safely inside) to have a first response option ready.

- Carry Extras in Strategic Locations: You might consider keeping multiple units: one on your person and perhaps one in your car or workplace (subject to legality and workplace rules). Having a backup pepper spray in your glovebox or desk means you’re still armed if you happen to not have your EDC unit on you. Just be mindful of temperature in cars (don’t keep it in high-heat spots long term). Some people keep a larger canister at home for home defense and a small one for daily carry. Just remember to periodically check and replace all of them as needed. It’s also wise to let close family or roommates know where a communal spray is kept and how to use it, in case they ever need it.

In summary, carry your OC spray in a way that you can deploy it at a moment’s notice. Practice reaching for it and bringing it into use. Treat it as an extension of your awareness – when you’re on alert, the spray should be in your hand or instantly reachable. The next sections will discuss using your awareness and verbal skills (often referred to as the pre-fight or “managing unknown contacts” phase) – during those phases, your pepper spray is ideally already in your hand or at least mentally “on deck” as an option.

Defensive Mindset and Pre-Contact Management

Physical tools like pepper spray are incredibly useful, but mindset and awareness are your first lines of defense. Effective use of OC spray (or any self-defense measure) starts well before you press that trigger – it begins with recognizing potential threats, maintaining a safe distance, and having the resolve to act decisively. This section covers how to identify danger cues (pre-assault indicators), overcome denial, use positioning and verbal skills to your advantage, and integrate a flashlight for added safety. These concepts are often taught in “Managing Unknown Contacts (MUC)” training and are crucial for avoiding trouble or setting yourself up to use pepper spray successfully.

Recognizing Pre-Assault Indicators: Criminal attacks don’t come out of a clear blue sky – there are usually warning signs if you know what to look for. Bad guys often display subtle (or not-so-subtle) behaviors and body language cues while they size you up or position for an attack. Here are key indicators:

- “That Doesn’t Look Right” – Trust Your Gut: Your intuition is a powerful alarm system. Many victims later report that they had a feeling something was wrong just before an attack, but they ignored it or rationalized it away[37]. If a person or situation gives you that weird vibe – maybe the person is loitering, watching you too intently, or approaching in an odd manner – listen to those internal pings. Don’t dismiss a sense of unease as paranoia or rudeness. Often your subconscious is picking up on subtle cues of danger that your conscious mind hasn’t yet processed. As mentioned earlier, if something feels off, it probably is. One instructor’s mantra is: “If it don’t look right, it ain’t right – period.”[10]. Give yourself permission to prioritize your safety over social niceties. It’s better to err on the side of caution than become a statistic. Those early gut feelings are part of your pre-need decision-making – act on them by increasing distance, preparing your spray, or leaving the area entirely.

- “Grooming” or Masking Behaviors: Attackers often exhibit nervous, ritualistic movements as they psych themselves up. They may touch their face, nose, or head repeatedly – e.g. wiping their nose, rubbing their eyes, covering their mouth, or brushing back their hair even when it’s not needed[38]. These are known as grooming cues or pacifying behaviors. Essentially, as the criminal’s stress spikes (knowing they’re about to commit violence and risk consequences), their subconscious tries to hide their stress by “masking” – literally covering their face or making self-soothing motions[39][38]. If you see someone doing these actions in context (like a man approaches you to ask a question, but he’s repeatedly touching his face or rubbing his neck while scanning around), it’s a red flag. Other examples: pulling up a mask or bandana, adjusting a hood obscuring their face, or putting on sunglasses at night. These could be attempts to conceal identity or hide facial expression, which honest people generally don’t do in normal encounters. Clenching of fists or jaw, and noticeable vein pulsation in temples or neck can also signal adrenaline. The key is looking for a cluster of unusual behaviors – one face scratch alone might be innocent, but face-touching combined with other cues (furtive glances, closing distance) is likely pre-attack behavior[40].

- Incongruent or “Interview” Behavior: Criminals often “interview” a potential victim – they’ll approach with some seemingly innocent pretext to test your awareness and willingness to resist. This could be asking for the time, directions, money, or attempting to engage in small talk. Pay attention to what their body is doing versus what their words are saying. If someone approaches asking for a light but is looking around over your shoulder (scanning for witnesses or cops), that’s incongruent – a major warning sign[41]. Similarly, if the person is trying to get you to prime a distraction (like looking at a map or checking something) while they maneuver, be wary. A classic is the “target glancing” tell: the criminal’s eyes repeatedly dart to something of yours – your phone, purse, wallet, or even your body/jewelry – while trying to keep casual conversation[42]. They are basically checking out what they want to grab. For instance, you ask a panhandler how you can help and you notice he keeps glancing at your watch or the open door of your car. That’s a clue he’s planning his move[42]. Also be alert to predatory movement patterns: someone positioning around or behind you, or two people subtly boxing you in from different sides. If a person or group alters their path to intersect yours with no legitimate reason, assume possibly hostile intent.

- “Shark Bumping”: This term describes when a predator tests boundaries with small intrusions – much like a shark bumping its prey before the bite. In human terms, it could be relatively benign requests or minor violations of your personal space to see how you react. For example, a stranger might deliberately brush against you or ask a random favor (like “Can I use your phone?”) to gauge if you’re an easy target. If you reward these “bumps” with compliance or distraction, the real attack may follow. The presence of multiple pre-assault indicators together strongly suggests you are being set up[43][44]. Two or three little things (say, the person is overly nervous, comes too close, and tries to get you to look at something) are enough that you should transition to action – either escape or prepare to fight.

Overcoming Normalcy Bias and Denial: One of the biggest enemies to personal safety is denial. As humans, we have a tendency to default to “everything is fine” and to avoid believing that bad things could be happening right now. This is known as normalcy bias – the assumption that the situation is normal and will remain normal. Criminals exploit this; they rely on the fact that many victims will hesitate, doubting their own instincts (“Surely this guy isn’t going to attack me here, right?”) until it’s too late. Train yourself to trust your intuitive alarm and act on it. As the saying goes, “Listen to your sixth sense; it’s your early warning system.” If you get that creepy feeling or notice those pre-attack cues, do not start rationalizing them away (“He’s probably just out for a jog…maybe he isn’t following me even though he’s been behind me on three turns…”). Acknowledge the possibility of danger and take proactive steps. It’s far better to err on the side of caution and be mildly embarrassed later for overreacting than to be caught in an assault. Remember, attackers count on victims being caught in denial and hesitation. By the time you have absolute proof of hostile intent, it might be too late. As one expert succinctly put it: Victims almost universally report some bad feeling beforehand; don’t rationalize it away – act![37]. If you suspect you’re being targeted, prepare your pepper spray, start implementing escape or defense measures (discussed below), and be ready to use force if needed. You won’t lose anything by being ready, and you might save your life.

Maintaining Distance (“Micro-Ranging”): If a threatening situation is developing, distance is your best friend. Pepper spray and other tools have an effective range – use it to your advantage, not the attacker’s. Don’t let a suspicious person close the gap to within arm’s reach of you. A concept from MUC training is “micro-ranges,” meaning always be mindful of exactly how many feet are between you and a potential threat. Most pepper sprays are effective at 6–10 feet; you ideally want to spray an aggressor before they can reach you with a punch or knife (which is about 3–4 feet). If someone is approaching and setting off your alarms, you should be moving to keep or increase that distance. This can involve taking steps back while you talk, or even better, lateral or arcing movement. Rather than backing straight away (which can be dangerous if you trip or run into something), practice “arcing” away at an angle[45]. By circling, you force the person to adjust to you, and you can move towards a safer position (like toward a lighted area or a barrier between you). In a training context, instructors have students work on arcing footwork to maintain distance while engaging with an approaching partner[45]. This also helps if there are multiple potential threats; you don’t want to back yourself into a corner or between two attackers.

- Set Boundaries Early: It’s perfectly okay – in fact, necessary – to tell an unknown person not to come any closer if they are making you uncomfortable. You can extend your arm in a “stop” gesture and say firmly, “Stop right there, please,” or “That’s close enough.” You might feel rude doing this, but better to be rude than robbed or worse. Many assailants “interview” by closing distance gradually, hoping you won’t object. Do not be polite about your personal space. If someone ignores two or more commands to keep distance, that’s a huge red flag that they likely have ill intent. Be loud and clear – “Back up! Stay back!” – if necessary. This not only communicates to the person that you see what they’re doing, but also could attract attention from others (witnesses) which deters criminals. As one trainer says, enforce your boundaries even if it feels impolite. Your safety > their feelings. It’s wise to maintain at least a two-arm’s-length distance from any stranger who approaches you unexpectedly. And if you can’t because they blitz in, that’s a near-immediate trigger to defend yourself (spray or otherwise).

- Don’t Get “Jammed Up”: In normal daily interactions, we often stand fairly close to people out of politeness, but with strangers in isolating environments, keep a buffer zone. If you’re using an ATM and someone comes and stands right behind you, politely but firmly ask them to give you space. If you’re walking and someone is paralleling you very closely, slow down or change course to create space. Many of us have a habit of not wanting to offend by moving away – but predators exploit that. It’s actually socially savvy and safe to maintain a bit of distance in public with people you don’t know. Think of it like defensive driving: you want enough following distance to react if the “car” in front (person near you) does something sudden. If an attacker can get within grappling range, you’ve lost one of the major advantages of pepper spray (distance!). So use your feet to keep that advantage. In training, students are often shocked to see how fast a person can cover 10 feet – often under a second. So the more you can extend that reaction gap, the better. If you need to, move in a way that forces them to either hang back or make their intentions obvious. For example, step around a bench or parked car – this can put a physical barrier or at least make them change direction to follow, confirming your suspicions.

Verbal De-escalation and Boundary Setting: How you talk to a potential assailant can influence the outcome. A well-known strategy is to “fail” the criminal’s interview – basically, make yourself a hard target through confident, non-submissive communication so they decide to abort. Here are some tips:

- Polite but Firm Initial Response: If a stranger approaches with a question or request (the classic setup), respond briefly and assertively. For instance, if someone asks, “Hey, you got a dollar?” or “Can I talk to you for a minute?”, a good default reply is something like: “No, sorry. I can’t help you.” Say it in a clear, unwavering voice – neither aggressive nor meek. This does a couple things. It establishes that you’re not an easy mark (you’re comfortable saying no), and it gives a benign person an answer so they can move on. Avoid getting into a conversation or giving excessive excuses (don’t say “Sorry, I only have credit cards” – that invites continued engagement or challenges). A simple refusal is best. Many criminal encounters begin with the target playing along out of politeness – predators count on that. By being willing to say no and disengage, you’re removing their opening gambit. If the person truly needed legitimate help, they’ll generally accept the first “no” and leave; if they persist or get agitated at your refusal, that’s a sign of malintent.

- Use Confident Tone and Posture: While speaking, project confidence. Stand tall, shoulders back, eye contact (to the extent you’re comfortable – some advice says make eye contact to show confidence, others say don’t because it can be seen as a challenge; a neutral direct look is fine). Keep your hands up in a non-threatening but ready position – for example, you can gesture with your hands as you talk, which incidentally puts them near chest level (this is sometimes called the “interview stance” or “fence” – hands up, open-palmed, appearing conversational but actually ready to block or strike if needed[45]). Use a calm but strong voice. Even just saying, “Hey man, keep your distance,” with authority can make an aggressor think twice. Many attackers want an easy victim – someone who appears weak, lost, or submissive. By failing the interview – i.e., not giving them the compliance or fear they seek – you may convince them to look for an easier target.

- Do Not Engage in Insults or Escalating Language: While you want to be firm, avoid outright trash talk or insults that could escalate the person’s aggression. For example, yelling “Get lost, scumbag!” might provoke a confrontation that could have been avoided. Instead, be assertive without being antagonistic: use statements of fact or commands (“Leave now.” “Back away from me.”) rather than name-calling. You can be loud if needed – in fact, a loud, commanding “Stop!” or “Back up!” is a good tactic, as it may startle the person and draw attention from others. The key is the content and tone: you are setting a boundary, not engaging in mutual hostility. Your words should convey “I am aware of what’s happening and prepared to respond”, not “I’m eager to fight you.” This not only keeps you legally on better footing (you don’t want witnesses hearing you initiate threats or excessive profanity), but also psychologically may keep the situation from spiraling. Many muggers will abort if they sense the target is alert and not easily intimidated – they prefer the element of surprise and a victim who freezes. By verbally responding confidently, you’ve signaled you’re not going to freeze.

- Confirming Hostile Intent: One useful side-effect of issuing clear commands is that it forces the other person to show their intentions. If you say “Stop, don’t come any closer!” and the person keeps coming or ignores you, then you have essentially confirmed this is likely an attack. A normal person with innocent intentions would usually stop or at least explain themselves if they truly meant no harm (“Oh sorry, I didn’t mean to scare you, I’ll stay back here…”). But if they just keep closing distance or say something manipulative like “Aw, come on, I just want to talk,” while still advancing, they’ve tipped their hand. This can help you mentally green-light your defensive response: you gave a chance for them to back off, and they chose not to. At that point, you can be fairly sure that whatever is coming next is not good, and you are justified in preparing to use pepper spray or other force. In some jurisdictions, this kind of clear boundary-setting can also play in your favor legally – you tried to de-escalate and they persisted, establishing them as the aggressor.

- Practice a Few Phrases: It might sound silly, but practicing your verbal challenge in advance can make you more effective under stress. In the mirror or with a friend, rehearse saying commands like “Stop right there!” or “Don’t come any closer, I’m not interested!” with a strong voice. This helps overcome the adrenaline that might otherwise leave you speechless. It’s similar to how police are trained to give loud verbal commands. You don’t want the first time you assert yourself to be during an actual threat – train it a bit so it comes out naturally when needed.

Using a Flashlight for Long-Range Awareness and Deterrence: A bright tactical flashlight (typically 200+ lumens these days) can be an excellent complementary tool to pepper spray. If it’s dark out, illuminate the areas around you as you walk – criminals love darkness and hiding spots. By shining a flashlight into parking lot shadows, between cars, or into shrubbery near a path, you send a clear message: “I’m alert and not an easy target.” Many seasoned criminals will actually back off if they suspect you might be law enforcement or otherwise prepared – and a flashlight is often associated with police or security. In a sense, you are taking away their element of surprise and possibly even their anonymity (they don’t want to be seen clearly). If someone is lurking, hitting them with a beam from a distance can make them think twice about approaching.

A flashlight can also be used defensively at the moment of an encounter. If a stranger is approaching at night and you’re uncomfortable, you can raise your light and flash it directly in their eyes (without necessarily blinding them permanently, of course – just a momentary flash). A 300+ lumen light aimed at someone’s face will cause them to squint or look away, giving you a psychological and visual edge. This is a great setup for deploying pepper spray. Imagine: it’s dark, a sketchy individual comes toward you – you shine your flashlight in their eyes and yell “Stop! Back up!” As they flinch from the light, you can have your pepper spray out and ready. If they still advance aggressively, you spray them. The flashlight does a few things: it buys you a second of disorientation on their part, it helps you aim your spray (you can see them clearly and even use the beam as a pointer), and if you do spray, the attacker’s pupils are likely dilated from the light and their eyes already irritated, possibly enhancing the OC effect. In police training, using a light in conjunction with pepper spray is common in low-light situations for exactly these reasons.

Even outside of direct confrontations, carrying a flashlight at night is just smart. It lets you spot potential threats from further away (e.g., see that someone is standing beside your car or loitering in an alley you’re about to pass). It signals to any would-be assailant that you’re not an easy, unaware victim (bad guys prefer darkness – shining a light is like saying “I see you”). Many self-defense experts consider a good flashlight one of the best everyday safety tools, right up there with pepper spray. And unlike many weapons, a flashlight is legal virtually everywhere and has plenty of innocent uses. So, incorporate it into your personal safety routine: when conditions are dark, flashlight in one hand and pepper spray in the other (or readily accessible) makes for a powerful non-lethal combination.

Deployment Techniques and Tactics

So you’ve done everything right so far – stayed aware, tried to avoid trouble, but the moment has come where you need to use your pepper spray to defend yourself. Now it’s all about execution. This section covers how to deploy OC spray effectively: aiming, firing technique, engaging the target, and handling common scenarios. Remember, like any defensive tool, practice and presence of mind are key. You don’t want the first time you spray pepper spray to be during an actual attack – if possible, practice with an inert training unit or at least rehearse the motions. Let’s break down the major points:

Target the Eyes and Face: The primary target area for pepper spray is the attacker’s face – specifically, the eyes, nose, and mouth. OC spray works best when it gets into the eyes (causing them to slam shut and tear up) and is inhaled (irritating the respiratory tract). So, you should aim for the eyes first and foremost. Don’t worry about being too precise under stress – generally, if you hit anywhere on the face, the effects will radiate to adjacent areas. A hit to the forehead will drip down into eyes, a hit to chin or mouth will still rise to the eyes and nose. The saying is “spray ’em in the face, let it go to work.” Mentally, you might imagine drawing an X-shaped pattern across the attacker’s face as you spray, especially if using a stream. This increases the likelihood of coating both eyes. With a cone mist, simply center it on the face; the spread will cover the eyes/nose region. Do not bother spraying the chest or weapon – unlike a gun, pepper spray doesn’t “stop” by pain except in the sensitive areas. Someone can fight through OC on their skin or torso, but nobody fights well with a face full of it.

If the attacker is armed (knife, bat, etc.), still focus on the face, not the weapon. The immediate goal is to make them physically incapable of continuing their attack by taking away vision and causing overwhelming burning sensation. Pro-tip: Aim for the eyebrows or upper eyes, especially with a stream, because gravity will make the liquid drop into the eyes. Some trainers say “Aim for the eyebrows, spray in a horizontal line”. A direct hit in the eyes is great, but if you aim just a touch high, you ensure coverage and that excess spray drips down. Also, hitting the forehead/eyes means some spray will likely be inhaled through the nose as well.

One more consideration: effective range. Know the range of your spray (e.g., 10 feet). If you spray from too far, it may not reach or could disperse, and you’ll waste precious shots. If you spray too close (say within 2 feet), there’s a high chance you’ll get backsplash (spray ricocheting onto you) or you might not get the full mist pattern. Ideally, use it at a range of about 4–8 feet if possible – that’s typically the sweet spot for full effect before they’re on you. But if you have to use it at close quarters, do it – just be aware you might catch some yourself (and be mentally prepared for that).

Aiming and Grip (“Thumb as Your Front Sight”): In the stress of an attack, fine motor skills degrade, but aiming pepper spray is fortunately not as exacting as aiming a firearm. Still, you should practice pointing and shooting quickly. The general advice is to use your thumb to press the spray (not your index finger) because this grip gives you a more stable aim and better retention of the canister[36]. Think of your thumb as the trigger finger and also the “front sight” – meaning you point the unit where your thumb goes. When you pull out your spray, don’t hold it like a perfume bottle with index finger on top; instead, make a fist around it and put your thumb on the actuator. This way, your fist and wrist align naturally with your target when you extend your arm. It’s much like pointing your index finger – except here your index finger wraps around and your thumb does the pressing. A big benefit is it’s harder for someone to slap it out of your hand from the front, because you’ve got a solid fist on it[36]. Also, if they try to grab it, your grip is stronger in that orientation.

When aiming under duress, it can help to aim for center of face (imagining the bridge of the nose). If you have a flashlight on the suspect, you can use the hotspot of the light as an aiming reference. In daytime, pointing with your support hand finger while spraying with dominant hand can also help index (though this requires some coordination; be careful not to spray your own hand). If using a stream, remember that a stream might hit a small area – so you might need to sweep it across the eyes. A common taught technique is the “X” or zig-zag: start at one side of their face and spray across to the other, then a downward diagonal and back. This increases coverage. With a cone mist, you don’t really need to sweep – just a steady burst directed at the face will envelop it.

Keep your arm slightly bent and spray from a stable stance. You don’t want to be so close that you extend your arm fully into their reach (they could grab your arm). A bent elbow also reduces the impact if they rush you – you can recoil or strike if needed. Importantly, avoid spraying into the wind if you can at all help it. If there’s a breeze, try to maneuver so it’s at your back or sideways. If you must spray into wind, do it and then immediately move or angle away to avoid blowback. Some instructors suggest a quick “burst and laterally move” tactic: spray a burst, then side-step or arc to flank the attacker, then spray again, etc. This forces the attacker to react and also can get you out of the path of any return spray droplets.

Proper grip with thumb on top ensures better control and accuracy when firing OC spray[36]. The image above demonstrates the ideal hold: a firm fist around the canister with the thumb used to depress the trigger. This grip naturally aligns the spray with your target and helps prevent the canister from being knocked away or dropped. In practice, point your thumb at the attacker’s face and press. If you have practiced even a little, this will direct the stream/mist where it needs to go.

Spray in Short Bursts, and Assess: A common rookie mistake is to hold the spray down continuously, emptying the can in a single, possibly ineffectual blast. In most cases, it’s recommended to spray in controlled bursts of about 1 to 2 seconds[46]. A quick burst to the face, then pause half a beat to see if it’s effective, then burst again if needed. Why short bursts? Firstly, pepper spray doesn’t need a ton of liquid to work – a little goes a long way if it hits the eyes. Secondly, if you hose someone non-stop, you may actually “wash off” some of the OC you just applied. The liquid can start to drip away, especially if you spray a huge volume, potentially reducing its effectiveness[46]. Also, continuous spraying can create a bigger cloud that might engulf you as well. By doing short bursts, you conserve ammo and give the OC a moment to start taking effect. Often a single one-second burst right into the eyes will cause a person to jerk back, close their eyes, and start experiencing pain. That’s your chance to stop spraying and see if they are stopping. If they are still a threat (say they’re wiping and cursing but still coming), hit them with another burst. Once the attacker’s face is coated and they are reacting (eyes closed, turning away, etc.), cease spraying[46]. There is no benefit to drenching them head to toe – your goal is achieved once their eyes slam shut and they’re distracted by pain. Additional spray beyond that point yields diminishing returns and just wastes your supply or increases contamination in the area.

Many pepper spray canisters will discharge completely in 5-10 seconds of continuous use. You don’t want to use it all up at once and be empty-handed if the first spray didn’t stop them completely. By using measured bursts, you can typically get multiple engagements out of one can. Real law enforcement data shows that about 85-90% of subjects stop aggression after one or two bursts of OC. If yours doesn’t, you might have to spray more or switch tactics (which we’ll discuss in follow-up actions). But definitely avoid the instinct to hold the trigger down in panic. It’s understandable in the moment, but try to remember: spray, evaluate, spray again if needed. One way to ingrain this is through practice – if you get a training spray, practice doing a quick burst and then moving.

After you spray, move! Don’t just stand static admiring your work. Either move backward (if something still coming at you) or preferably off-line (to the side). This forces the attacker, who is now likely flailing and half-blinded, to have to reorient to find you. Use this opportunity to either escape or prepare a secondary defense (e.g., draw another tool or get into a fighting stance if pepper spray alone isn’t enough). A sprayed attacker might still have a momentum – some can lunge a bit or swing wild punches. You want to get out of their immediate reach while the spray takes full effect (which usually intensifies over a few seconds as the burn compounds).

Handle Multiple Threats or Bystanders: If you face multiple attackers, prioritize who is nearest or most aggressive and spray them first. Then turn to the next. Pepper spray spray can have a deterrent psychological effect on others – when they see their buddy screaming and clawing at his eyes, they may back off immediately. But if not, dish out a dose to each as needed. Be aware of your backdrop; try not to hit bystanders (though if it’s you or them, you must protect yourself). If you do accidentally hit a friend or bystander with some overspray, they’ll suffer temporarily but it’s not permanent – address that after you’re safe. In an ideal scenario, you move such that the attackers line up and you can spray them all with one arc of mist. If you have a cone fogger, one blast can affect a couple of people if they’re close together. With a stream, you might need to sweep across multiple faces in one go.

Dealing with Wind or Enclosed Spaces: As mentioned, always consider wind. If outdoors, position yourself with the wind at your back when deploying if you can choose. If you suddenly get a faceful of your own spray due to wind, don’t panic – remember that pepper spray affects everyone, including you. If you do get exposed, you might feel the burn and blink uncontrollably, but the attacker likely has a much higher dose. Try to fight through it enough to keep moving to safety. If indoors (like inside a vehicle or room), know that spraying will contaminate the area. It might bounce around off walls. If you’re in a car and someone is reaching in or already partly in, blasting them will likely also cover you in a tight space – but it’s still better than being strangled or worse. Just be mentally ready for the burn (we’ll cover decon in the next section). Fun fact: dry chemical fire extinguishers can be used similarly to pepper spray in enclosed spaces to create a smokescreen and irritate – it’s been suggested as a classroom defense tool. But if you use something like that, definitely short bursts and be prepared for zero visibility.

Close Quarters Tactics: What if the attacker is already on top of you or grabs you suddenly? Can you still use pepper spray? Yes, but you must be careful not to spray yourself. If someone has grabbed you, try to turn your face away and then spray upward toward theirs. Even if you can’t see, just spray between you – the goal is to get OC into their eyes from any angle. A trick taught in some self-defense classes is if you’re grabbed, you can “index” the spray against the attacker’s body (touch the can to them if needed to know where to spray) then aim upward to the face. Example: they bear-hug you; you manage to get your spray out and press it against their shoulder or chest, then angle it up toward their neck/head and fire. You might both get hit, but again, you’ll survive it. In a bear hug or grapple, even spraying wildly can cause enough discomfort to loosen their grip.

Better yet, if you see someone is about to physically grab you, and pepper spray deployment is too slow at that exact instant, create a bit of space with a quick physical counter then spray. For instance, a technique taught in MUC is an eye jab or palm strike to the face of the attacker as they get close[47]. You’re not trying to brawl, just quickly stun or push them off for a second. As their hands reflexively go up or they recoil, you immediately draw and spray them fully. Even a half-second break in their attack can let you effectively employ the OC. Another scenario: if someone is throwing punches at you, you might cover up or evade briefly, then when you see a moment (their eyes open or they take a breath), you spray toward their face. In extremely tight quarters (like inside a car or elevator scuffle), sometimes spraying the general area is fine – everyone will feel it, which might break the fight momentum. Just be sure to close your eyes or hold breath briefly if you must fire super close to yourself.

Lastly, hold on to your spray can. Once you’ve sprayed the assailant, do not toss the can aside (unless it’s empty and you have another weapon). An attacker might try to knock it out of your hand – grip it tightly. If they manage to take it, you could get sprayed with your own can (bad outcome). Some advanced training covers using the canister as an impact weapon if necessary (many OC cans are hard and can be fist-loaded to strike). While that’s beyond scope here, know that a small can in your fist can add oomph to a punch if it comes to that. Ideally though, the spray does the work and you can then escape or escalate to another force option if absolutely required.

In summary: Aim for the eyes, use your thumb, spray in bursts, and move. Pepper spray, when used with these tactics, is a very potent fight-stopper. It requires presence of mind to deploy under stress, but that gets easier with a little practice and the confidence that you have a plan. Next, we’ll discuss what to do after you’ve sprayed someone – dealing with the aftermath, both legally and in terms of decontaminating yourself or others.

Post-Deployment Considerations

You successfully pepper-sprayed your attacker – what now? The fight might not be entirely over, and there are aftermath issues to address. This section covers effectiveness follow-ups, legal responsibilities, and decontamination after using OC spray, as well as a note on its use against animals.

Expect and Plan for Partial Compliance: Pepper spray is highly effective, but it’s not a sci-fi instant knock-out. Be prepared that the attacker may not instantly drop the second the OC hits them. In many cases, especially with a good hit, they will immediately shield their face, turn away, and start retreating or stopping – effectively out of the fight. But there are instances (due to adrenaline, drugs, or sheer willpower) where an attacker may continue to flail or charge for a short time even while the spray is working. Think of OC as turning the dial up on an attacker’s “difficulty level” – they might still be fighting, but at a greatly reduced capacity (can’t see well, can’t breathe well, in pain). Have a follow-up plan. This could be: once you spray, transition to another force option if they are still a threat – for example, create distance and draw a firearm or a blunt weapon if you carry one, or prepare to physically fend them off if they close in. Or it could be escape: the moment they reel from the spray, you run like heck to safety. Often the best follow-up is to remove yourself from the situation entirely, since the OC bought you time. If you do carry a firearm, many self-defense experts highly advocate carrying pepper spray as well (for exactly scenarios where lethal force isn’t initially justified). If you had to spray and it didn’t stop them and now they’re still posing a deadly threat, you have shown you attempted a less-lethal measure first. You should only escalate to deadly force if you genuinely believe it’s necessary to prevent death or great harm, of course – but if it is, you’ve laid a better groundwork for legal defense by trying OC first.

In practical terms, after spraying, get off the line of attack and keep observing the attacker. If they are on the ground or fleeing, great – you can retreat and call police. If they still advance, give another burst to the face. If you somehow lost the spray or it’s empty and they’re still a threat, be ready to fight with hands or other tools. Many times, though, you’ll see that the attacker’s will is broken even if they physically haven’t collapsed. People often mentally quit once they’re hit with OC because the pain and fear of blindness takes over. They may cuss and threaten, but often they don’t effectively pursue. Keep commanding them – “Get back! Stay down!” etc., while you move away.